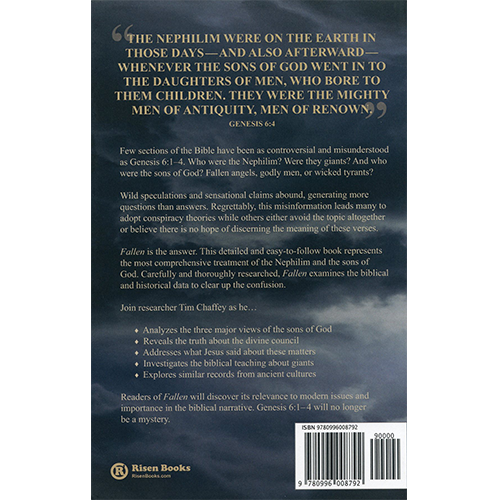

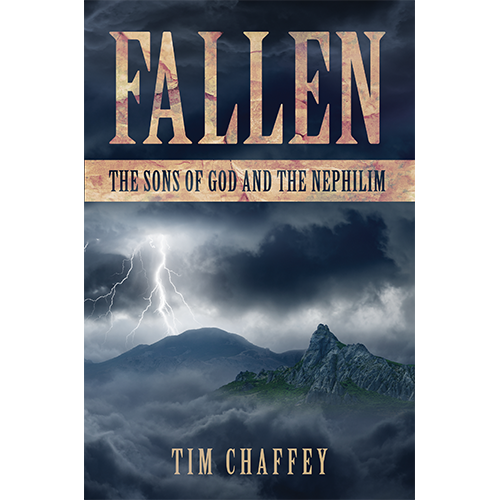

[fusion_dropcap boxed=”no” boxed_radius=”” class=”” id=”” color=””]O[/fusion_dropcap]ur first two articles in this series introduced the topic and addressed the first of three major views on the sons of God in Genesis 6:1–4. If you missed those, you can read them at these links:

The Sons of God and the Nephilim — Part One

The Sons of God and the Nephilim — Part Two

For a bit of context, here is our passage again.

And it came about, when mankind began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born to them, that the sons of God saw the daughters of men, that they were beautiful. And they took for themselves wives from any they chose. And Yahweh said, “My spirit will not remain with man indefinitely, in that he is flesh; his days will be one hundred twenty years.” The Nephilim were on the earth in those days—and also afterward—whenever the sons of God went in to the daughters of men, who bore to them children. They were the mighty men of antiquity, men of renown. (Genesis 6:1–4)

The Royalty View

In this third article, we provide an overview of the second major view, which has been called the Dynastic Rulers or the Royalty View. Those espousing this position claim that the sons of God were kings or other nobles who considered themselves as divine or were regarded as divine by their subjects. These tyrants forced women (“the daughters of men”) to join their harems. Thus, their major sin was polygamy.

Within this view, the Nephilim are usually believed to be the offspring of these unions, so they were princes or sons of other powerful men. As such, they could rightly be called mighty men and men of renown. However, this does not account for the Nephilim being described as giants, and those holding this opinion do not usually consider them to have been giants.

Perhaps the two most common Royalty View arguments center on two potential clues from within the Bible. First, Nimrod is called a gibbor (“mighty one” or “mighty man”), the singular form of the term used to describe the Nephilim in Genesis 6:4 (gibborim – “mighty men”). We know that Nimrod was also a ruler (Genesis 10:10–12), so there is a connection in Genesis 10 between a king and the term for “mighty one.”

Second, the term for sons of God in Genesis 6:2 and 4 is bene ha’elohim. Some Bibles have occasionally translated the term ’elohim as judges in Exodus 21:6 and 22:8–9 (NKJV) or rulers in Psalm 82:1 (NASB). So if ’elohim can rightly be translated as rulers or judges, then the sons of these individuals would likely become rulers as well.

Problems with the Royalty View

These arguments may seem compelling at first glance, but things are not always what they appear. The assertion that ancient Near Eastern kings pronounced themselves as divine is not as solid as many claim. The ancient Mesopotamians believed that the concept of kingship came from heaven, but they did not, for the most part, view their kings as divine.

This final problem with the Royalty View we cite here is quite devastating to its premise. The context of Psalm 82:1 demonstrates that ’elohim cannot be referring to human rulers or judges. Here, God had taken His stand in the divine council, and He pronounced judgment on the gods. The remainder of the psalm and Jesus’ citation of it in John 10 demonstrates that these “gods” were heavenly beings who were being judged for their failure to carry out God’s orders. If ’elohim cannot legitimately be understood as referring to human rulers or judges, then the Royalty View loses its best argument and cannot provide a plausible interpretation of Genesis 6.

Conclusion on the Royalty View

The Royalty View handles the text in a more consistent manner than the Sethite View discussed in our previous article. However, like the Sethite View, it has serious shortcomings. These two views are appealing to many readers who strongly object to the Fallen Angel View, but they cannot be substantiated by a careful study of the biblical text. In our next installment, we will look at the most popular and most controversial position, the Fallen Angel View.